Seven Deadly Sins, Part 7: Sin

If you can define sin, you can control people.

Sin is the great trick.

Long before governments, before police, before HR policies, platforms, or “community standards,” the powerful thought up of a way to keep you in line - sin. If you can define sin, you can control people. And what counts as a sin depends entirely on who is in charge.

To some, desire is a sin. To others, hunger is.

For some, telling the truth is a sin; for others, staying silent is.

Sin is a behavioural management tool: move this way, speak that way, want less, need less, don’t stand out. Do what we say or you’ll burn in Hell for all eternity, or in modern terms, you’ll be cancelled.

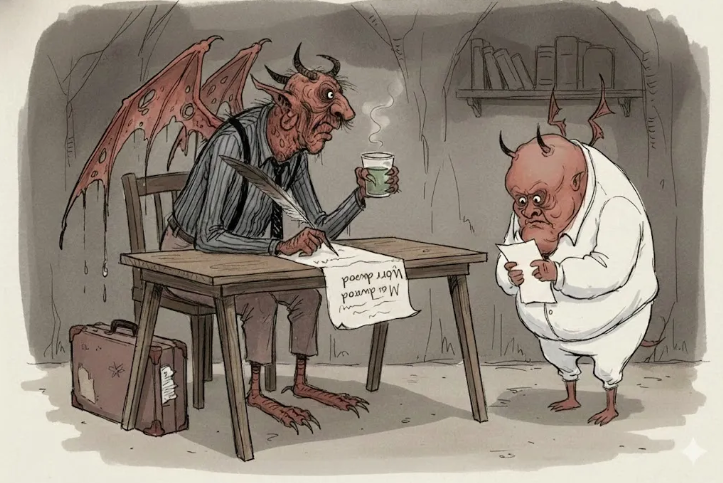

In the C.S. Lewis book, The Screwtape Letters, an old demon writes to his nephew, “Indeed the safest road to Hell is the gradual one--the gentle slope, soft underfoot, without sudden turnings, without milestones, without signposts,...Your affectionate uncle, Screwtape.”

Screwtape at his writing desk

The book is a satire, not a scripture, Old Screwtape doesn’t advise his nephew, Wormwood, to tempt people with wild wrongdoing. He simply encourages him to make them to shrink.

To keep their confidence low. To keep quiet.

To keep them obedient by default.

You don’t need violence if people police themselves.

You don’t need a tyrant if guilt does the work for free.

Sin was supposed to name harm.

Now it names anything that inconveniences the powerful.

It’s a “sin” to be angry.

It’s a “sin” to be poor.

It’s a “sin” to be loud, chaotic, ambitious, queer, addicted, neurodivergent, or simply visible in the wrong way.

We used to be warned of divine punishment.

Now we’re warned of algorithmic penalties, getting reported, getting cancelled, or getting quietly cut out of the loop. Different tools, same outcome: compliance.

Screwtape’s trick, as literature, not doctrine, was never about tempting people into dramatic wrongdoing. It was about shrinking them. “It is funny how mortals always picture us as putting things into their minds; in reality our best work is done by keeping things out.” Screwtape was advising his nephew to keep out confidence, keep out curiosity, keep people so unsure of themselves that they don’t notice the rules were invented by someone else.

That’s what guilt is for: to stop you asking why things are the way they are.

But listen,

When someone calls what you did a “sin,” it doesn’t reveal anything about you.

It reveals what they want to control.

And if sin is an invention, you can stop believing it.

If sin is a story, you can rewrite it.

If sin is a cage, you can step out of it.

If sin is a trick, you can refuse to perform it.

The most dangerous idea in any system built on guilt is this:

The things we’re taught to be ashamed of, desire, hunger, ambition, anger, defiance, are the very things that keep us alive.

Modern society runs on guilt because guilt is cheap.

It’s easier to convince people they’re broken than to fix the world they live in.

It’s easier to say you are the problem than to confront the systems creating the harm.

But the moment you stop apologising for being human?

The whole thing starts to crack.

Because guilt only works if you accept it.

Shame only works if you agree with it.

“Sin” only works if you believe it’s real.

Take away that belief, and the whole spell collapses.

And once it collapses, you see it clearly:

the line between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” was never divine. It was just someone’s preference for your behaviour.

You don’t defeat a system like this by being pure.

You defeat it by refusing to play its game.

Screwtape’s “demons” were never supernatural.

They were psychological; pressure, doubt, shame.

They were structural; rules designed to keep people small.

They were political; obedience sold as virtue.

And when you stop treating your humanity as something to apologise for, the trick falls apart.

The cage door opens.

And you finally get to live a life that belongs to you, not to someone else’s rules.