Drugs 2: Choice

If drug use is a choice, then suffering must be deserved. That is a lie.

We’re often told that drug use is a choice. You chose this. You asked for it. If you didn’t want to die of an overdose, you shouldn’t have taken drugs.

But “choice” isn’t the same for everyone. We’re not all choosing from the same menu.

We’re not all choosing from the same menu.

For some people, choice looks like therapy, time off, or a clean break somewhere new. For others, it’s choosing between medication and rent. Between using and withdrawal. Between numbness and collapse. Between surviving today and paying for it tomorrow.

Money buys buffers: private space, flexible work, stable housing, safer supply, lawyers, second chances. Poverty strips those away. What gets called “poor choices” are often just the only choices the poor get to make.

What gets called ‘poor choices’ are often just the only choices the poor get to make.

If you listen to shock jocks and politicians, you’d be forgiven for thinking drugs are floating around in the air, waiting for people to calmly decide to become dependent, as if addiction were a preferred lifestyle choice.

The story falls apart the moment you look at who uses drugs casually. The bank worker, the accountant, the builder with a bag on the weekend isn’t proof of bad choices. They’re proof that the story only applies to certain people.

It’s only when drug use collides with poverty, when there’s no buffer, no privacy, no exit ramp, that it suddenly becomes a character flaw. Same drugs. Different class. Different verdict.

For the targeted drug user, the ones you’re warned about, drugs don’t arrive first. Conditions do. Poverty. Trauma. Violence. Chronic pain. Loneliness. Boredom. Racism. Family history. Mental illness. Unsafe housing. Policing. Shame.

By the time drugs show up, the choice has already been shaped.

For some people, it was laid out long before they were even born. And they’re never allowed to forget it.

The drug hypocrisy is easiest to see in the United States, where it’s made explicit. Some states decriminalised; others imposed brutal sentences for simple possession. Black and Latino users are punished far more harshly than white users for the same behaviour. Poor white users are treated differently to white users with money.

Women are judged more harshly again. Drug use is framed as a personal failure, and motherhood turns that failure into monstrosity.

When Nancy Reagan told a generation to “just say no,” drug use was framed as a simple preference, chocolate or vanilla. That simplicity hid the truth. It erased poverty, trauma and inequality, recasting a social problem as a personal moral failure. That framing didn’t just stigmatise; it justified mass incarceration, and it landed hardest on marginalised communities.

In Australia, the campaigns were calmer, dressed up as education and prevention. Harm reduction existed alongside them, needle and syringe programs, methadone, later injecting rooms, and that mattered. It kept people alive.

But even here, the story underneath was the same. Drugs were framed as bad decisions, not predictable responses to unequal conditions. Responsibility was individualised. Blame was just delivered more politely, with better pamphlets and a Medicare logo.

If drug use were really about choice, outcomes wouldn’t track so neatly along lines of class, race and postcode. But they do. Over and over. Everywhere.

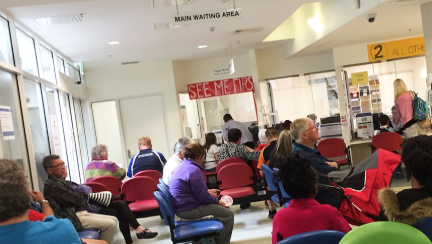

And once you’re known for having a drug problem, your future choices shrink even further. Jobs disappear. Housing disappears. Stability disappears. Even in the emergency department, a person labelled a drug user may be refused pain relief despite clear suffering. At that point, the word choice becomes almost insulting.

Image: ABC News, emergency department waiting area

Most people who use drugs are trying to cope, not rebel. They’re trying to feel normal, not reckless. They’re trying to get through a day that has already decided to be hard.

And yes, people make decisions. Of course they do.

But decisions made under pressure, threat, pain or desperation aren’t free in the way we pretend they are.

Choice without options isn’t really choice.

Both major parties in Australia have leaned on the same basic story: drug use as a personal failing, not a product of conditions. The Coalition has been more explicit, openly linking drug use to unemployment, welfare dependency and moral weakness, backing drug testing and punitive income management. Labor’s language is softer, more health-based, but the underlying frame often stays intact. Law and order still dominates. Harm reduction is cautiously tolerated rather than fully embraced. Responsibility is quietly pushed back onto individuals.

If inequality doesn’t matter, nothing has to change.

Different tone. Same logic.

If drugs ruin your life, it’s because you made the wrong choices, not because of poverty, trauma, housing, policing or inequality.

Because if drug use is about choice, then inequality doesn’t matter.

And if inequality doesn’t matter, nothing has to change.

That’s the real function of the myth.

This is the second entry in a short series on drugs, harm, and the stories we tell ourselves about them.