Seven Deadly Sins, Part I: Money

Money can’t buy happiness, but it’s more comfortable to cry in a BMW than on a bicycle.” Origin unknown

Cash, dosh, dough, bread. We all use money, we all need it, and we’re all trapped by it. Little shapes our lives more than money; especially when you haven’t got any. It’s expensive being poor.

It’s always been this way. As soon as people realised they could trade meat for milk, shiny beads for fur, or bread for sex, someone wanted more than everyone else. More beads, more fur; there ws never enough.

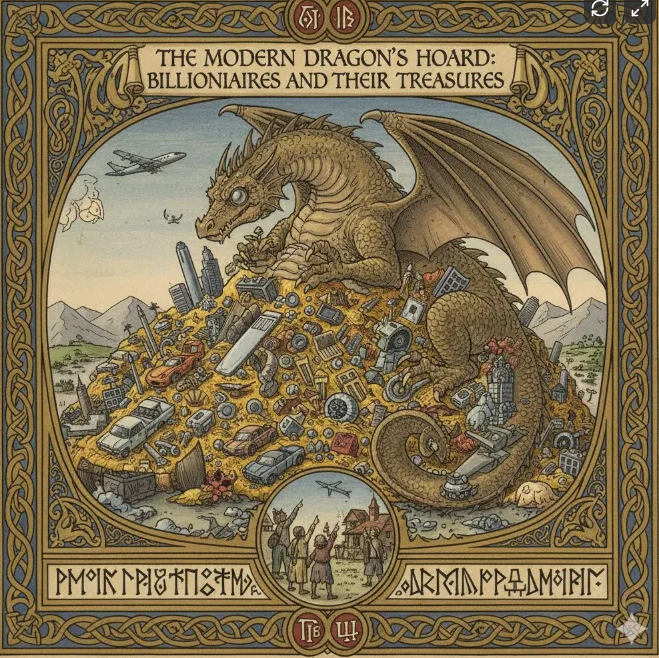

For many of the richest people, it’s not even what they can buy with it, it’s about getting more. More than they could spend in a thousand lifetimes. The wealth held by a few people today would be unimaginable to your grandparents’ generation.

In the 1960s, oil tycoon J. Paul Getty was considered the richest man alive, worth about a billion US dollars, roughly $11.5 billion today. That’s pocket change compared to the fortunes floating around now.

A billion dollars is a thousand million; enough to stack a tower of hundred-dollar notes more than a kilometre high. If you spent a thousand dollars a day, every day, it’d take you three thousand years to run out.

Between December 2019 and December 2021, the richest 1 percent, those with over US$1 million in net wealth, captured about two-thirds of all new wealth (~US$26 trillion of ~US$42 trillion), twice as much as the bottom 99 percent (Oxfam International). That means about 80 million people captured double the wealth gains of the other 7.9 billion people.

Things began to spiral out of control with Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan’s trickle-down economics. They claimed that giving tax breaks and benefits to the wealthy would eventually help everyone. A rising tide lifts all boats. The only problem with that was that it was complete bollocks, and they knew it. The rising tide didn’t lift all boats. The rich got bigger boats, and the poor had to fight to keep their heads above water.

In practice, the rich don’t spend or invest in ways that help the everyday worker; they park their money in assets, buy back their own stock, or stash it offshore. Corporations use tax breaks to boost shareholder dividends, not give pay rises. The “flow” stops at the top, circulating among those who already own everything. Meanwhile, governments slash public spending to cover the revenue they just gave away, gutting healthcare, education, and welfare. Trickle-down doesn’t grow economies, it siphons them upward.

Today, when we have years, no, decades of proof that it doesn’t work, we still hear the same lines about supporting the wealthy. For example, a 2020 study by David Hope and Julian Limberg (London School of Economics) analysed major tax cuts for the rich across five decades in 18 wealthy nations and found that the rich get richer while unemployment and economic growth are unaffected.

Politicians champion tax cuts for doners, the “wealth-generators” as they’re often called. These wealth-generators risk little. They pay little or no tax, they’re often subsidised by us, and if they fail, they get bailed out by us. I can’t remember who said this, but they “privatise their profits and socialise their losses.”

“Ah”, I hear the right say, “but they worked for their money and pulled themselves up by their bootstraps”. This fairytale often leaves out the fact that they had special advantages, like family money and connections, good education, access to opportunities that many others don’t have.

This myth makes it seem like anyone can become rich if they just work hard, ignoring the real barriers that most people face. The idea that it just takes a positive attitude and a bit of elbow grease and you’re assured of a good life: money, quality healthcare, a comfortable home.

The grotesque obscenity of wealth on display. The “History Supreme”, owned by Malaysia’s richest man, Robert Kuok, the $4.8 billion yacht, made from 10,000kgs of solid gold and platinum.

The people at the top, who make the rules tell you that no matter where you start from, you have the same chance of succeeding as everyone else. Once you believe that anyone can succeed if they try hard enough, it becomes easy to blame poverty on personal choices, moral failings, or laziness. This is why you’ll often hear politicians talk about bludgers or welfare cheats.

The people on top call it opportunity, individual freedom, or a fair go if you have a go. The truth is that we don’t all have the same opportunities. Modern Neoliberal politics focuses on free markets, rewarding those who can leverage them. This creates economic inequality and insecurity, leaving many behind. The game is already over, and chances are you’re not a winner. The dice was loaded, the deck was stacked.

The unequal distribution of wealth remains a persistent problem, with a small percentage of the global population holding a large share of resources. This disparity has significant real-world impacts, limiting access to healthcare, education, and opportunities for many.

Wealth brings influence, allowing the rich to shape policies, politics, and societies to their benefit. This concentration of power can lead to corruption, as those with financial means manipulate systems to maintain or increase their wealth and control. The wealthy often live in worlds far removed from the experiences of the majority, deepening societal divides.

This issue is evident in practices like corporate lobbying and political campaign financing. When a wealthy few sway decisions affecting millions, it undermines the democratic process, leading to disillusionment and eroding trust in institutions. Policies that favour the affluent exacerbate inequality and perpetuate a cycle of privilege.

To tackle this imbalance, we need to rethink how we tax the wealthy. Fairer tax policies can help redistribute wealth, ensuring the rich pay their fair share. A 2% levy on the super-rich, those worth over $1 billion, would generate between $193 billion and $242 billion in tax revenue each year, according to French economist Gabriel Zucman, who drafted A Blueprint for a Coordinated Minimum Effective Taxation Standard for Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals for the Brazilian G20 presidency.

Of course, the super-wealthy, as a rule, oppose paying a cent more. Bernard Arnault, who presides over the LVMH empire of 75 fashion and cosmetics brands including Louis Vuitton and Sephora, is worth $186.1 billion USD. A 2% tax would cost him about $3.72 billion, leaving him $182.4 billion to play with. To put that in perspective, Arnault could spend $1,000 every minute of every day for 347 years before running out. And he’s still complaining that a wealth tax would be “unfair.” Cry me a river.

By increasing taxes on the wealthy, we can fund essential services, reduce inequality, and create more opportunities for everyone, moving us toward a fairer and more equal society.

Failing that, we could always eat the rich.