THE STORY OF COCAINE, PART TWO: MIRACLE AND MYTH

Cocaine became a cure-all for everything that could be imagined: pain, melancholia, nervous exhaustion, impotence, and neurasthenia, the mental cost of industrial speed.

In 1884, European powers sat around a table in Berlin and carved up Africa between them. In Australia, the Victorian Women’s Suffrage Society formed to demand “the same political privileges for women as now possessed by male voters.” And in Vienna, an Austrian ophthalmologist named Karl Koller dripped a few drops of cocaine into his own eye, making it temporarily insensible to pain and changing surgery forever.

Within a month, news of Koller’s discovery had spread around the world. Within six, cocaine was being used in surgery on eyes, throats, ears, and in childbirth.

Cocaine became a cure-all for everything that could be imagined: pain, melancholia, nervous exhaustion, impotence, and neurasthenia, the mental cost of industrial speed.

At the Vienna General Hospital, a young, unknown, but fiercely ambitious neurologist was convinced he had stumbled on a miracle. In Über Coca, the 28-year-old Sigmund Freud praised it as a treatment for depression, indigestion, exhaustion, and morphine addiction. He gave it to friends. He took it himself. Like much of the medical world at the time, he mistook stimulation for healing and momentum for proof.

Pharmaceutical companies moved fast. Cocaine appeared in throat lozenges, toothache drops, wines, nerve tonics, asthma powders, and “female remedies”, the Victorian umbrella term for any condition men were uncomfortable naming. It was prescribed for menstrual pain, hysteria, and nervous collapse. There was no meaningful regulation, no long-term safety data, no informed consent as we would understand it today. Just optimism, profit, and an unshakeable faith in chemistry.

In Atlanta, John Stith Pemberton, a Confederate veteran wounded in the Civil War and left addicted to morphine, created an alcoholic coca wine called French Wine Coca in 1885, marketed to treat pain, fatigue, and addiction itself. When Atlanta went dry under temperance laws in 1886, he stripped out the alcohol and kept the drugs, reformulating it with coca leaf extract and kola nut. He called it Coca-Cola.

For a brief, dangerous moment, cocaine became the perfect symbol of Western modernity: purified, concentrated, industrialised, the ancient Andes crushed into a white promise of control.

And everyone wanted some.

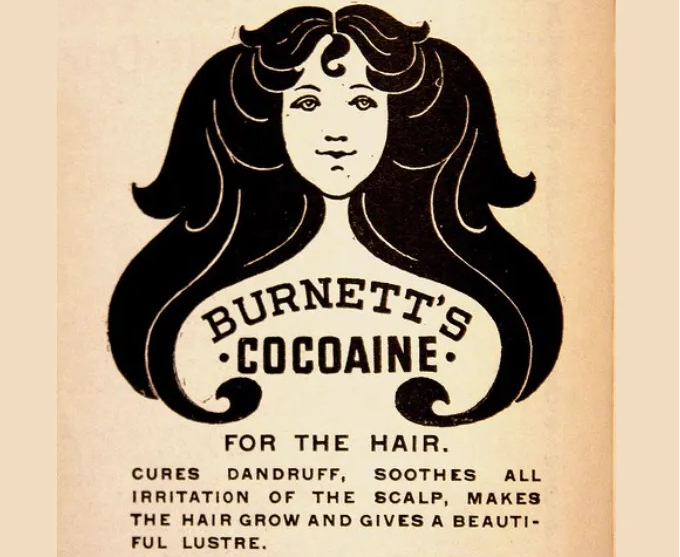

Burnett’s Cocoaine for the hair. 1896

It wasn’t long before the cracks in the perfect picture began to show. Patients who had come for pain returned for the drug itself. Surgeons began to note agitation, tremors, hallucinations, and heart palpitations. What had looked like alertness became fixation. What had looked like energy began to look like damage.

Doctors started publishing uneasily worded case reports. Dependence. Collapse. Mania. Death. Cocaine was still being prescribed, still being sold, still being praised, but the footnotes were changing. The confidence was evaporating.

Freud noticed too, though more quietly. By the late 1880s he had begun distancing himself from his earlier claims. Friends he had encouraged to use it struggled. Some suffered lasting harm. Freud had urged his close friend and colleague, Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, to use cocaine to treat severe pain and morphine addiction from a botched thumb infection. Instead, Fleischl-Marxow became addicted to both morphine and cocaine, suffered horrific psychosis and physical collapse, and died in 1891. Freud was haunted by his friend’s death for the rest of his life. He said, “I was making frequent use of cocaine at that time ... I had been the first to recommend the use of cocaine, in 1885, and this recommendation had brought serious reproaches down on me.”

And yet the machine did not stop. Tonic bottles kept rolling off production lines. Advertisements kept promising. The market did not correct itself. It accelerated.

The myth was cracking. But it would take something far uglier than medical doubt to finally break it.

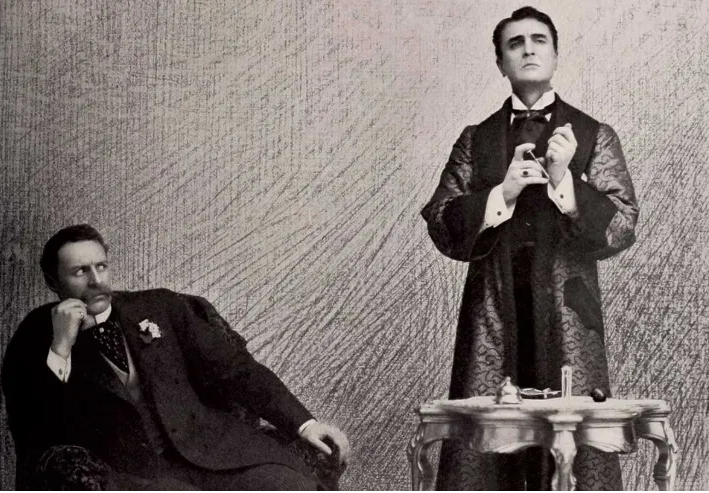

Sherlock Holmes, played by William Gillette, and his hypodermic. From a stage adaptation of Sherlock Holmes at the Garrick Theatre, London, 1899.

By the 1890s, cocaine had slipped its leash and was turning up in bars, brothels, port towns, and back rooms. It moved through dock workers, entertainers, labourers, the rich and the poor. In “The Sign Of Four”, Arthur Conan-Doyle wrote of Sherlock Holmes using a seven-per-cent solution of cocaine to relieve the boredom of not having a case to work on.

Newspapers noticed the increased problems associatd with cocaine use. Headlines hardened. The tone shifted from curiosity to alarm almost overnight. Cocaine was now a problem in the streets. Stories multiplied. Some true. Many exaggerated. All of them drenched in fear.

In the United States, cocaine was framed as a drug of Black men, tied to invented myths of superhuman strength, violence, and moral collapse. The image of the Black man assaulting white women was deliberately pushed by white supremacists still fighting the Civil War by other means, long after Gettysburg and the Wilderness had fallen silent. Cocaine became the perfect fuel for existing racism, a chemical excuse for brutality and control.

The Ku Klux Klan seized on cocaine panic as propaganda to justify lynching, segregation, and armed policing.

In Europe, cocaine stayed framed longer as a bohemian and medical problem, not a racial threat. It moved through artists, writers, doctors, and nightlife before it ever became a police issue. It lived in Paris cafés, Berlin cabarets, London patent medicines. Concern grew about addiction and collapse, but without the same lynch-mob hysteria. Regulation crept in through medical boards and pharmacy laws, not race terror and armed policing.

What began as a medical experiment had become a commercial product and a public threat. Decisions about it were no longer being made in laboratories, but in courtrooms and police stations.

What happened next would have nothing to do with health, and everything to do with power.